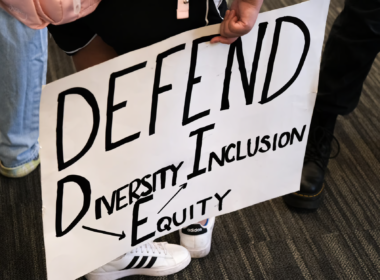

Governments Not Immune to Racism. The Shameful Truth.

Surrounded by a metal fence, with some 30 video cameras and a controlled entrance, the Via Salone 323 camp, a segregated settlement constructed on the periphery of Rome and authorized by Italian authorities for Roma population, is “like a concentration camp, there is no tattoo, but there is a card to enter and exit,” as one resident of the camp said before asking if the law allowed “to keep all these people in this way in such a space.” To Roma people, a subgroup of the Romani people, an ethnic group originating from India, the exonym Gypsies is often attached carrying within itself an invitation for discrimination, racism and exclusion.

The Via Salone 323 formal camp is, according to the 2012 report by the European Roma Rights Center and the Associazone 21 Luglio to the UN Committee on Racial Discrimination on Italy, the most representative of the policy adopted by Municipality of Rome toward the Roma people.

Between AD 500 and AD 1000, the Romani started migrating from India westward. They reached the Balkans in 14th century and Scotland and Sweden in 16th century. They are now widely dispersed living primarily in Eastern and Central Europe. It is estimated that some 12 million Romani people live in Europe with significant populations in France, Spain, Italy, Ukraine and Russia. Romani organizations estimate this number to be close to 14 million because many Romani choose not to register in official censuses.

Large concentrations of Romani people are also in Middle East and in the Americas. They first immigrated to North America in colonial times, to French Louisiana and Virginia. In the 1860s, they started arriving to the United States in larger numbers, mostly from Britain.

After their arrival to Europe, Romani people were soon subject to hostilities, forced labor or expulsion from the communities and so they started to move eastward to Poland and Russia. During World War II, between 220.000 to 1.5 million disappeared in concentration camps, according to various estimates.

The 2012 report by the European Roma Rights Center and the Associazone 21 Luglio to the UN Committee on Racial Discrimination on Italy addresses discrimination of Roma in areas of housing, violence and access to education and healthcare. It gives among other the picture of Roma living today in extreme poverty and inadequate housing, often with no access to water and sanitation.

Currently, some 1,100 people live in Via Salone 323 in 198 container houses with limited space. Only half a mile from the camp is an incinerator for toxic waste, and there is neither hospital nor pharmacy nearby.

The same report also talks about the Italy’s “state of emergency in relation to nomad settlements” that entered into force in May 2008 and gave extraordinary powers to special state authorities or “commissioners for the construction of all actions necessary to overcome the state of emergency” in several Italian regions. Among the powers afforded to special state authorities were monitoring Roma camps, identifying and recording residents, displacing individuals to camps that are formally monitored and evictions of “informal settlements.”

Even though the Italian Council of State ruled in November 2011 that the “state of emergency” and the presidential decrees for emergency situations were not lawful and were illegal, the authorities in Italy are not paying attention, with Municipality of Rome continuing to build new formal camps, according to the report. Seven formal camps are in Rome alone, with some 3,000 Roma people.

Classification of Roma as “nomads” by Italian authorities in spite of the fact that almost all Roma in Italy are sedentary effectively represents the institutionalization of discriminatory policies that are preventing inclusion of Roma into society.

In mid-February, the European Roma Rights Centre (ERRC) stated in Washington, DC that the violence against Roma was escalating. And in March, it expressed concerns about attacks on Roma in Lyon, France. Many families were evicted from a school building after their previous housing had been burned down and according to ERRC and local activists French authorities have carried out evictions of these Roma families repeatedly.

Similarly, indigenous people, some 350 million of them around the world, with 5,000 languages in more than 70 countries, are living on the fringes of society, isolated, marginalized and deprived of basic human rights, says UN. With no access to basic social services, often victims of dispossession of their lands, they are also vulnerable to the impacts of climate change.

In Colombia alone, where some 41,000 indigenous people live, 27 indigenous groups are at risk of disappearing, says the country’s Constitutional Court, mainly because of the internal armed conflict that started in 1964 and that pitted the country’s armed forces mostly against two guerrilla groups, the National Liberation Army (ELN) and the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Columbia (FARC). Caught in the armed conflict, several thousands of indigenous people fled their lands to get away from violence and vicious treatment by different armed groups. The loss of their land has destroyed their communities and their identity. As one Siona man said that to lose the land was to lose the self. UN says on its website that the story of Colombian indigenous peoples is the story the “world should hear more about.”

Despite the UN Declaration on the Rights of indigenous People and international law that entitles indigenous groups to protections from forced displacements, too many indigenous groups around the globe have been and are still being displaced.

There is no end to these stories. Attacks on houses where immigrants live, attacks

by skinheads against Roma people that resulted in injuries, attacks of “vigilante groups” that were never prosecuted, marching of paramilitary groups in the fascist black uniforms in settlements populated by Roma on the pretense of preventing crime in the presence of police that did not stop such demonstrations, youth throwing Molotov cocktails into a house inhabited by Roma, arson attacks on places of worship, beatings and stabbings of migrants in the street, creation of “migrant-free zones”–these are just a few incidents from July 2011 report of the Special Rapporteur on contemporary forms of racism and on the implementation of the UN General Assembly resolution. Appointed by Commission on Human Rights, Special Rapporteur in the discharge of his/her mandate transmits communications and appeals to States on violations with regard to racism and discrimination, embarks on fact-finding country visits and prepares and submits annual reports to Human Rights Council. Special Rapporteur is independent from any organization or government and serves in his/her individual capacity.

The relationship between conflict and racism is a “deep-rooted” and “well-established,” said head of UN Human Rights Office Navi Pillay on the International Day for the Elimination of Racial Discrimination last month pointing out that many studies have indicated that one of the earliest signs of potential violence is the blunt disregard for the rights of minorities. The big problem is that the earliest signs of prejudice are too often ignored and the countries and international community only react later when more sinister signs develop, Ms. Pillay also acknowledged.

The influx of immigrants from the Third World countries to Europe, Australia, the United States and Canada brought new challenges giving the cultural dialogue a new meaning of appeasing or resolving conflicts and maintaining peace between communities.

According to 2011 report of the Special Rapporteur, extremist political groups and parties are blaming specific groups, such as migrants, refugees, Roma, indigenous people, and asylum-seekers, for the socio-economic problems of the general population and are inciting the discrimination against them.

Former Special Rapporteur on modern-day forms of racism Githu Muigai says that extremists often view themselves as the only legitimate national identity of their country and are gaining more supporters because of the current economic crisis.

Countering extremism remains a challenge for too many countries. At the 2001 World Conference against Racism, the countries recognized that racism-based political platforms were incompatible with democratic principles. And yet, Special Rapporteur received since 2001 many reports showing that extremist organizations have gained influence in many countries, according to the UN.

In some countries, extremist political parties have embraced new more moderate strategies and tones to position themselves firmly on the political landscape and in order to be elected they have even formed alliances with more traditional political parties.

In national as well as regional parliaments, the number of seats that are occupied by representatives of extremist political parties has increased in recent years, says UN.

The most alarming impact of the extremist parties and groups is their infiltration into political programs of democratic parties under the scheme of combating terrorism and illegal immigration and defending ‘national identity,’ states already the 2006 study by the Special Rapporteur on contemporary forms of racism.

The 2006 study also points out the extent to which the political agendas are focused on “national,” from “defending the national interest” and “national preference” to preserving “national heritage.” This rhetoric quickly “becomes the new political expression of discrimination” because of its “non-recognition of multiculturalism” and “identification of all those the nation needs to defend itself against.”

The Special Rapporteur however also warns in his 2011 report that some laws on extremism are being used in some countries to deny the political opponents the democratic legitimacy by characterizing them as extremist. He says that all individuals “including those deemed radical” should have the right to participate in the “public affairs” and “to vote or to be elected.”

At the 2001 World Conference on Racism, the Secretary General of the Conference Mary Robinson underscored that the follow-up to the Conference would be the key involving the responsibility of governments and civil society in implementing the conclusions and final documents of the Conference.

When this March the United Nations General Assembly observed the International

Day of Remembrance of the Victims of Slavery and the Transatlantic Slave Trade, the international diplomatic community had once again to call for action to eliminate all forms of modern-day slavery, among them racism and racial discrimination, human trafficking, child labor, forced marriages, sexual exploitation and the use of children in armed conflict.

In some countries, extremists and extremist political parties have been at the forefront of political attacks, most notably against Roma camps. Negative portrayal and stigmatization do not always and exclusively come from extremist and nationalist groups as is the case in Italy, France and elsewhere.

Stigmatization and violence have been rampant all over the world for decades. Ethnic extremism in Central Africa among the Hulu and Tutsi, violent conflicts among Croatians, Serbs and Bosnians in former Yugoslavia, Arabs and Jews in Israel, Tamils and Sinhalese in Sri Lanka–these are just a few ethnic conflicts of the last twenty years.

The President of the 2001 Conference on Racism Dr. Nkosazana Dlamini Zuma of South Africa had talked at the time of the Conference about the issues of reparations and apology saying that to most “apology did not mean money, it means dignity.”

Yet, the question remains if we are ready for apology at all.

Source: UN, UN Office of High Commissioner for Human Rights

Photo: DIMITAR DILKOFF