Today, we walk around with a movie studio in our pockets. Even a basic smartphone can film high definition videos and editing software can be downloaded on the App Store. Apps like TikTok and sites like YouTube rely on this accessibility for their content, and they have made millions by showcasing the video efforts of their subscribers. However, this newfound ease in movie making has not translated to the big screen. In fact, even as movie making has become easier, it has become more difficult to turn this accessibility into mainstream success.

Hollywood told Melvin Van Peebles that no one would ever bankroll a movie with an all Black cast, Van Peebles did not shelve the project. Instead, he decided to finance the movie himself. Armed with only $50,000, Van Peebles revolutionized filmmaking by making the classic Sweet Sweetback’s Badass Song. When he slammed up against regulations, Van Peebles got creative. He claimed that the movie was a pornographic film in order to keep filming. Van Peebles also couldn’t afford an official crew, but because he went outside the studio system, he was able to cast an all Black crew. Today, Sweet Sweetback’s Badass Song is credited with starting the blaxploitation genre, although the movie was not actually an exploitation film. By using his own money and defying official standards, Van Peebles was able to realize his goal of “show[ing] the faces Norman Rockwell never painted.”

Film is a powerful vehicle for social change, which is why it’s important to tell as wide a range of stories as possible. Partially for marginalized people, as they need to see images of themselves reflected in the wider media landscape, but also because privileged people can be introduced to ideas and experiences they hadn’t heard about before. Mainstream studios are reluctant to say anything that might generate controversy, let alone something that threatens the status quo. Since the beginning of mass media, this led to a severe lack of media about marginalized people and perspectives. Now that fewer and fewer corporations control media, it is difficult to find alternate viewpoints in mainstream cinema. Disney is not going to lend their name to radical ideas. As a result, filmmakers are forced to follow their own paths.

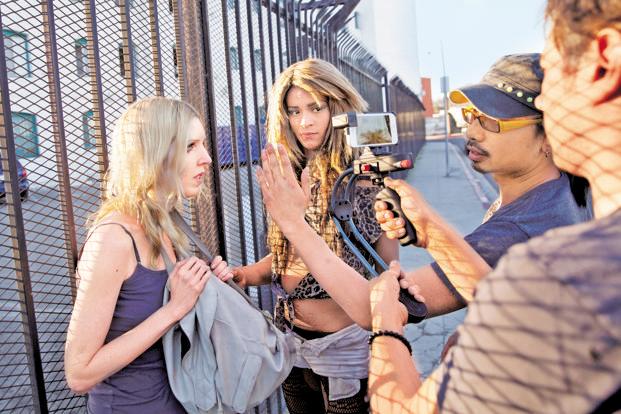

This is why guerilla filmmaking is so valuable. Guerilla films are movies that are funded by the creative team and operate outside of typical Hollywood institutions The genre emerged in the 1960s and 70s, when advancements in video technology made it easier for small-time directors to acquire and use cameras and other equipment. Guerilla filmmakers reject the idea that a massive budget is necessary to produce quality work. To save costs, they have a limited crew, few props, and often no filming permits. The name guerilla filmmaking evokes revolution, as “guerilla” warfare refers to an army composed of amateur soldiers and with no government backing. Like their namesakes, guerilla filmmakers do not rely on the system and forge their own paths.

Just as technological advancements birthed guerilla filmmaking in the 1960s, new forms of technology enabled a new generation of filmmakers. Everyone has a high resolution camera in their pocket and new editing software makes producing a movie even easier. Sites like YouTube give newer filmmakers a platform for their work. How-To guides like The Guerilla Filmmakers Handbook are professionally published, and websites from indiewire.com filmlifestyle.com offer advice on the subject. However, even as guerilla filmmaking has become more accessible, it has become increasingly hard for viewers to find. Numerous guerilla films like Zero Day, Four Horseman, A Dead Gay Guy, andGetting Away with Murders were produced in the past decade, yet they are not featured on any streaming service. The corporatization of the media chokes independent voices. Despite that, young filmmakers still embrace guerilla tactics in a concerted effort to democratize filmmaking in new and original ways.

Guerilla filmmaking gives the director more control over their work, so they can tell stories that no big name studio would touch. Marginalized groups use this opportunity to explore their own culture. The acclaimed director Darren Aronofsky’s guerilla film Pi focused on the Jewish community and Jewish mysticism, topics that would never make it past the gates of the big studios. Robert Rodriguez’s Mexico Trilogy started with El Mariachi, a guerilla film with an all Mexican cast. In Latin America, guerilla filmmaking became a crucial part of the Third Cinema, a movement that challenged imperialism in the region. The genre is also gaining popularity in East Africa and Southeast Asia. Queer directors, like Amadine Gay, explored the lives of African-European women in France. Because guerilla films do not require studio approval, they can be used to elevate voices that have been silenced.

Furthermore, guerrilla films challenge the nature of subjectivity in the media. Cinema is often held up as a true reflection of reality, but by offering new outlooks, guerilla films reveal that the stories we are told are not necessarily true. We live in a world of mediatization where technolog lets the media infiltrate every part of our lives. Thanks to streaming sites such as Netflix, Hulu, Disney+ we have unprecedented access to the media and due to this ubiquity, we have begun to tie our identities to media consumption. Because most of the media is controlled by corporations, the media is usually used to perpetuate oppressive structures. Guerilla filmmaking challenges these structures by shining a light on those who are most affected by them.